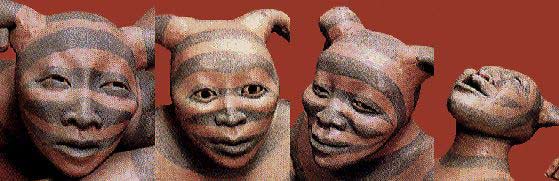

The image of this group of koshares (The Emergence of the Clowns) was used as an ad for the Heard Museum in Native Peoples Magazine. I had never visited there in the 11 years we lived in Tucson because we avoided Phoenix if at all possible. We invented all sorts of ways to drive around Phoenix when going to Flagstaff, California, Utah or Canyon de Chelly. Any other routes were preferable. Phoenix was Los Angeles moved to the Sonoran Desert. But this image told me that I must visit the Heard Museum.

After the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix ended, Steve and I drove into the center of the city and found the museum. The exhibit which included this sculpture had gone on tour! We were able to see another of Ms. Swentzell's groups, a pre-contact family sitting together and sharing their meal of beans and seeds harvested from the native plants. The closeness and interdependence of this family was clear from the way the individual pieces related to each other. I talked to many people at the museum about the Emergence of the Clowns group. Everyone I talked to there about the sculpture could only talk about what this sculpture meant to them, and how everyone who came through just stood in front of it captivated. In the museum shop they managed to find an old poster with the image of the clowns. The poster had been rolled up in a back room and was covered with dust, but I cleaned it carefully. It had only one fold near the bottom. They happily gave it to me gratis.

I followed the progress of that show around the country until it arrived at the Smithsonian in Washington. Steve and I chose a weekend and flew down solely for the purpose of seeing the clowns. If that had been all we saw, the trip would certainly have been worth it. The piece was overwhelming, even though they had it encased in plexiglass, perched on a white enameled stand, completely outside the context in which it was meant to exist. These men are emerging from the earth. In their eyes you can see the knowledge of all things human and earthly. You see joy; you see sadness; you see weariness; you see incredulity that the people have done it yet again! Are humans capable of learning?

How does she do that? The eyes are incredible, yet so simple. It is really the absence of the physical surface of the eyes that draws you deep into these souls. The Navajo artist Elizabeth Abeyta's sculptures do the same thing. The gestures are so simple and natural, but the feelings are unmistakable. These are humans who know full well all of the failings that beset man.

In the same show was an incredible painting by Helen Hardin in front of which I stood bewitched for 10 minutes at a time. I would return to it several times before being dragged away. The complexity of the image drew you in to the simplicity of the iconography beneath the surface. The image would hold me and not let go. Many of the other items were almost as incredible, carvings from the Northwest Coast, masks, paintings by artists I had not seen before, a Pablita Velarde painting of more complexity than those usually seen. It takes a lot to get me to Washington on a summer day, but this exhibit allowed me to ignore the climate and to immerse myself in the art and the souls, as illuminated through their art, of the Native American artists.

During the next year, I found myself passing through Santa Fe, and I visited the Institute of American Indian Art where the Alan Houser Sculpture Garden was newly installed. In one corner of the adobe walled yard in central Santa Fe, was a small group of young aspen trees. Standing just on the front edge of this grove was a life-size female koshare with her arms extended toward the world, looking forward with eyes that pierced the viewer. The one word title of this Roxanne Swentzell sculpture was Why? I could not walk away. I wanted to walk forward and embrace her but all the proscriptions of museums forbade me. I could not move, nor could I possibly answer. I finally tore myself away to see the rest of the sculptures, which included a half life-size pair of bronze figures by Nora Naranjo-Morse. The solidity and relaxed presence of this pair consoled me somewhat, but I had to return again and again to the female koshare whose one question of the world was "Why?" This sculpture has haunted me since that day.

In the Rain exhibit at the Heard Museum we saw a small, almost round koshare made as a canteen that Ms. Swentzell had made. Again the simplicity of the form and gesture and the intensity of the eyes was riveting. She is also known for her sculptures of women.

Roxanne's sculptural group, The Emergence of the Clowns, was also included in Exhibition VI of the series Twentieth Century American Sculpture at the White House.

Discussions by Discipline Experts on Emergence of the Clowns