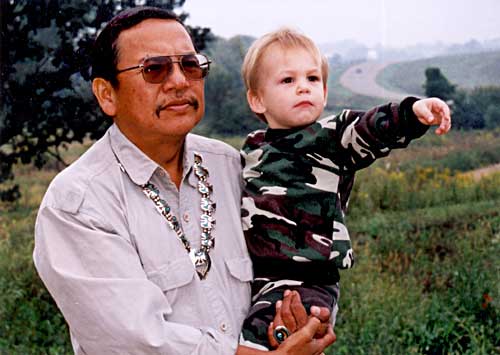

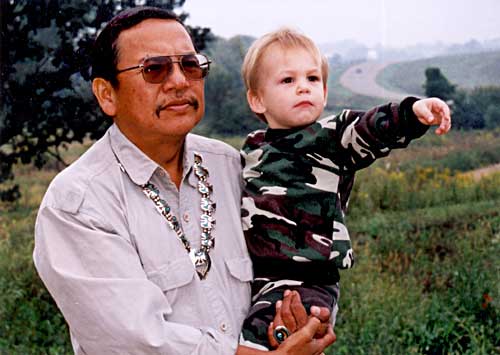

| Ray Young Bear |

|---|

| Home: Meskwaki Settlement, Tama Age: 50 Family: Wife, Stella. They are in the process of adopting five children. Books: Winter of the Salamander, The Invisible Musician, Black Eagle Child: The Facepaint Narratives, Remnants of the First Earth, and The Rock Island Hiking Club. |

Tama, Ia — Ray Young Bear constantly edits his life narrative — in poems. in conversation, in other dimensions, in his van.

Hopping in the Dodge, the Native American writer from the Meskwaki Settlement starts quickly with an opener.

"I run for tribal council every year," he says, pausing to clear the seat of papers.

"I'm never elected."

In 2 1/2 hours he will drive around the settlement and discuss his new poetry collection released this summer, the pending adoption of five children by him and his wife Stella, and his involvement in the new settlement school ready to open later this fall.

He'll part company with a discussion of psychic visions.

He still won't be done.

During the next several days he will send faxes to clarify life-changing events, from his new role as parent to his work with law enforcement on well known murders, to an evolving list of people he admires, which include well-known poet Robert Bly, pop singer Christina Aguilera and psychic detective Noreen Renier.

The final typed fax will include pen scribblings with arrows and question marks.

This is not to say Ray Young Bear is a flake. He is a writer, after all, and one of such high standing nationwide that scholars on Native American literature call him a "national treasure."

But he is as hard to grasp as a slippery fish out of the Iowa River that runs through the Meskwaki Settlement where he has lived nearly all of his 50 years and where his great-great grandfather negotiated to buy this land 145 years ago.

Young Bear's imagination unfolds like the landscape going past, gravel roads and timber groves of his youth that he points to out the van window.

Once he hammered out thoughts on an old typewriter from his perch in a trailer. Today he "voice types" notes into a computer from a new house on the hill, the blinking neon of the casino across the way.

What one is left with after editing is this: Ray Young Bear has deep connections to his past but is as modern a practitioner of contemporary culture as any writer, as easily tossing references to soaring hawks as cheap Grain Belt beer.

"He is a great modern poet," says Robert Gish, an expert on Native American literature at the University of New Mexico. He calls Young Bear's new book of poetry, "The Rock Island Hiking Club," (University of Iowa Press, $13) nothing less than breathtaking.

"He combines the power of indigenous voice with a modernist voice."

Young Bear's work is largely autobiographical. That, the poet says, is due to the wishes of elders.

"Much of what I say and much of what I write comes directly from the thoughts of my late grandmother," he says. "She encouraged my early efforts."

His grandmother coaxed him to learn English, to both speak and write it, although around his home the native tongue ruled. It was often thought to be the first step in full-scale assimilation, a sellout to Indians holding dearly to their culture.

"She wanted me to approach the greater Iowa population and tell them that it was the great clan of Old Bear that settled here and not a group of stragglers as history is wont to believe," says Young Bear, speaking slowly, editing each sentence. "ls wont the right word? Yes, W. . .O. . .N . .T."

Young Bear submerged himself in English words, which he plays off his tongue and on paper, finding their very sounds fascinating. As a young man, he wrote in the tribal newsletter his profound political statements on settlement life sacked with poverty and political struggles.

He was criticized, he says, because openness and freedom of expression are not prized on the settlement.

"My grandmother encouraged me not to dwell on other people's criticisms and continue my journey," he says.

In 1969, he met the poet Robert Thy at a writers conference and his life as a "word collector" began with newfound inspiration. He struggled to sell poems for a couple hundred dollars for grocery money.

His voice eventually gathered into a collection in 1980 called "Winter of the Salamander," followed 10 years later by "The Invisible Musician."

So extensive are his rewrites that only every third word survives the mauling.

In 1992, the opening work of his trilogy, the highly acclaimed autobiographical novel "Black Eagle Child: The Facepaint Narratives," propelled his career to an A-list Native American writer in demand at writing conferences and festivals.

The book followed his young alter ego Edgar Bearchild on the settlement "in the middle of nowhere encumbered with poverty and alcoholism" with a wit and play about modern life, poking fun at both Indian stereotypes and tribal foolishness.

Characters such as Junior Pipestar, a legendary medicine man who holds spiritual sessions in the Ramada Inn, highlight the odd cultural marriage of the Native American in a modern world.

"I've known a lot of writers," says Stephen Pett, who teaches creative writing and Native American literature at Iowa State University. "I don't know any writer who tries, without being affected, to be completely true to himself. He is serious and committed to his community and on the other hand is funny and really invigorated by popular culture."

Young Bear's quest has been clear, and not just in his writing: Save the traditions but not on horseback.

Young Bear stops the van at the settlement school he once attended. Its halls are narrow, the rooms small, and children are huddled around the desks, speaking in both the native language of Meskwaki and English. He says the struggle for a new settlement school has spanned 20 years and the new one just up the road is finally set to be open soon.

As a school board member, he has pushed hard for a school that can continue the Meskwaki traditions while educating youth on the larger world.

He doesn't shy from controversy. Few tribal members will offer public opinions of him. Jim Ward, who lives on the settlement, says most residents here keep their views to themselves.

"But somebody's got to say something," he says. "I think Ray speaks for some people."

When the casino opened in 1992, Young Bear was heard.

He demanded openness and accountability from tribal officials on the many changes brought about by new money and power coming to the settlement from casino profits. He led a dissident group to oust some tribal council members. He's often run for the council and always failed.

"The community loves Ray when he's wrong, and they dislike him when he's right," says his wife Stella.

Only days after the attack on America, politics take a back seat. The connections between past and present, between life and death, are thick in the air. Through his visions and dreams, he claims a special connection.

Young Bear is thinkõng of the passengers who thwarted hijackers on the jet that crashed in Pennsylvania. He is thinking of his grandmother's voice. He is haunted by the 1995 death of his brother, who was run over by a vehicle.

The visions of the dead come to him from the Lazy Boy, his metaphorical portal to either his writer's imagination or psychic ability, he's not sure which.

His vision of the future is no less inspiring. He is attempting to adopt five Meskwaki children, ages 1 to 9, who are in the custody of state officials. It's part of the tribe's quest to return children to the settlement. He is awaiting final approval.

'Young people want to live their lives with their people," he says. 'We offer our homes and our cars to children, and what they need is our culture and religion."

The opening poem in "The Rock Island Hiking Club" begins like this:

"Symbolically, they stand close together/as they have done through their lives/on the Black Eagle Child Settlement ...."

Interview published in the September 25, 2001 issue of the Des Moines Register.

Return to the Ray A. Young Bear website