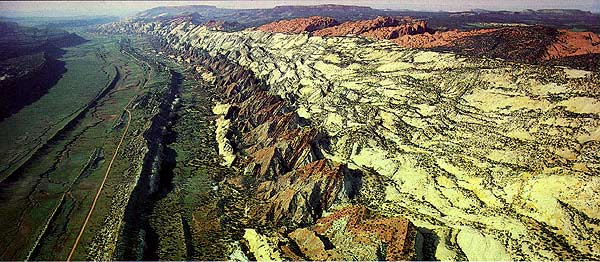

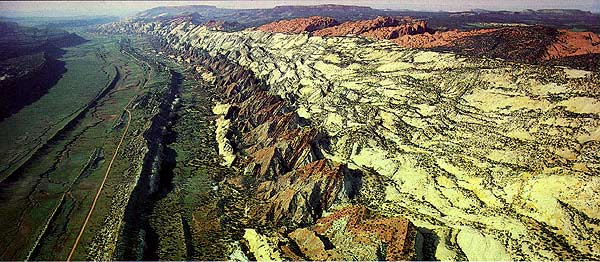

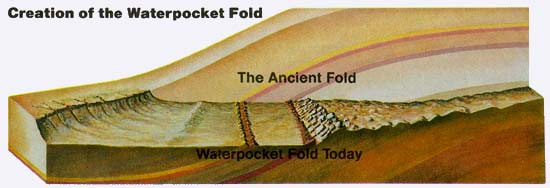

A giant, sinuous wrinkle in the Earth's crust stretches for 100 miles across south central Utah. This impressive buckling of rock, created by the same tremendous forces that built the Colorado plateau 65 million years ago, is called the Waterpocket Fold. Capitol Reef National Park preserves the Fold and its spectacular, eroded jumble of colorful cliffs, massive domes, soaring spires, stark monoliths, twisting canyons, and graceful arches. But the Waterpocket Fold country is more than this. It is also the free-flowing Fremont River and the big desert sky. It is cactus, jay, lizard, jackrabbit, juniper, columbine, and deer. It is a place where Indians hunted and farmed for more than 1000 years and, later, where Mormon pioneers settled to raise their families. It is the inspiration for poets, artists, photographers, and those who seek only to re-create themselves in the solitude and splendor of its vastness. The world of the Waterpocket Fold stretches for 100 miles . . . and beyond.

People of the little known but widespread "Fremont Culture" lived along the river as early as AD 700, sharing the rugged slickrock wilderness of the Colorado Plateau with the Anasazi who lived in the south. The Fremont people hunted and gathered their food, and grew corn, beans and squash, as well. When they mysteriously disappeared sometime after 1250 AD, they left behind traces of their life here. The rock art they painted (pictographs) and incised (petroglyphs) into canyon walls can still be seen in several places. Later, nomadic Utes and Paiutes hunted throughout the Waterpocket Fold country.

Explorers, Mormon pioneers, and others began to make their way into the valley of the Fremont River in the late 1800s. Settling beyond the valley required a trip across the rough terrain of the Waterpocket Fold. A narrow, rocky travel route that cut through the Fold was Capitol Gorge. One rock wall called the Pioneer Register is filled with the names of miners, settlers, ond others who passed through this canyon beginning in 1871. By 1917, the tiny Mormon community of Fruita was bustling on the banks of the Fremont. With skillful irrigation of the good soil of the valley, Fruita became well known for its productive orchards and the quality of its fruit. Flooding sometimes occured but the town was spared any serious destruction. After Capitol Reef National Monument (later to become Capitol Reef National Park) was set aside in 1937, the farmers and their families gradually moved away. The heritage of these pioneers is preserved in an old log schoolhouse, where socials, dances, and church meetings were once held, and in other structures scattered around the still-thriving historic orchards and fields of Fruita.

Today, the life along the Fremont River consists of the life of cottonwoods, willows and ash, which create a fresh ribbon of green each spring, and of Indian paintbrush, goldenpea, and other seasonal wildflowers. It is the life of animals drawn by the magnet of water: birds galore, from mountain bluebirds to migratory ducks, and mammals, from marmots to mule deer. But move away from the river - even just a few hundred yards - and the harsh, sparser environment of the desert dominates.

In the backcountry the desert dominates, and it stands in stark contrast to the Fremont River valley, a rare oasis. Less than eight inches of rain fall per year, most of it in late summer thunderstorms. These storms can turn dry, sandy washes into raging torrents, threatening some forms of life while sustaining others. Twisted, stunted juniper and piñon tree, which dot the landscape along with other hardy plants, are testimony to the severity of the desert. But many plants and animals are adapted for life here. In different ways, kangaroo rats, lizards, cactuses, and saltbush cope with the perennial water shortage of the desert. Some are experts at collecting and storing water; others at water conservation; some at both. Many animals move about only at night to escape the heat of day, so the casual observer can easily underestimate the richness of animal life in the desert.

Occasionally, pools of rainwater collect in eroded bowl-like depressions in the rock called waterpockets. Oddly, the tiny waterpocket is the namesake of the massive Fold that dominates the landscape. Bighorn sheep, bobcats - and even people - have quenched their thirst at these holes. At least one animal, the spadefoot toad, uses the waterpockets as places to live and reproduce. Eggs laid in the water hatch into tadpoles within days of a rain. Tadpoles that reach adulthood before the pools dry up repeat the cycle when the pools fill again. And life in the Waterpocket Fold country goes on.

See our map and guide reference section for trail maps and other useful information available from Maps.com.