Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee - TV - Dee Brown - HBO

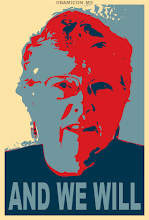

LOS ANGELES, May 8 — When the historian Dee Brown published “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” in 1971, it became an instant sensation. In an age of rebellion, this nonfiction book told the epic tale of the displacement and decline of the American Indian not from the perspective of the winners, but from that of the Indians.

But the fact that Mr. Brown’s work has been translated into 17 languages and has sold five million copies around the world was not enough to convince HBO that a film version would draw a sizable mainstream audience. When the channel broadcasts its two-hour adaptation of the book, beginning Memorial Day weekend, at its center will be a new character: a man who was part Sioux, was educated at an Ivy League college and married a white woman.

“Everyone felt very strongly that we needed a white character or a part-white, part-Indian character to carry a contemporary white audience through this project,” Daniel Giat, the writer who adapted the book for HBO Films, told a group of television writers earlier this year.

The added character is based on a real person: Charles Eastman, part Sioux and descended from a long line of Santee chiefs but who was sent away by his father to boarding school and then held up as a model of the potential assimilation of 19th-century Native Americans. But the film fictionalizes significant portions of his life. In the HBO version he dodges bullets at the Battle of Little Bighorn. In reality he was far away, in grade school in Nebraska.

Fictionalizing history has long been standard in Hollywood. But rarely do filmmakers directly hitch their historically inaccurate projects to revered works of nonfiction. Dick Wolf, an executive producer of the film who is best known for the “Law & Order” television franchise, defended the fabrications.

“This was not an attempt to do the Ken Burns version of the Indian experience,” Mr. Wolf said in an interview. “It is a dramatization, and we needed a protagonist.”

(The chief executive of HBO, Chris Albrecht, announced yesterday that he was taking a leave of absence after being charged with assaulting a girlfriend in a Las Vegas parking lot early on Sunday.)

At the time it was published, Mr. Brown’s epic, subtitled “An Indian History of the American West,” struck a chord in a country embroiled in a divisive war in Vietnam and still shuddering from the American military’s massacre in the village of My Lai. Segregation was dying hard in the South, and the American Indian Movement was ascending.

The story is a relentless tragedy, tracing the history of American Indian nations from 1860, shortly after the first new states extended into the “permanent Indian frontier,” through 1890 and the massacre at Wounded Knee, in what is now South Dakota. It became a blockbuster best seller and helped shape the way the history of the American Indians has been interpreted ever since.

For decades the book eluded attempts to turn it into a film, partly because of Mr. Brown’s distrust of Hollywood. At least two attempts by potential moviemakers to adapt the book failed. When the current producers optioned the book five years ago, Mr. Brown was in the last years of his life and, according to his grandson, did not believe anything would come of the project. (Mr. Brown died in 2002 at 94.)

Tom Thayer, the executive producer who originated the project, said the HBO team wrestled for months with how to boil down a book that spans 30 years and dozens of tribes into a 130-minute film.

“The book is basically an editorialized textbook,” Mr. Thayer said. “It doesn’t have a single narrative; it’s anthropological and episodic.” Therefore, he added, “we felt that to tell a story of that size, the Eastman character would be a great hand-holder for the audience.”

Many literary critics, and millions of readers, however, had little trouble following Mr. Brown’s story. Writing in The New York Times Book Review in March 1971, N. Scott Momaday, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, emphasized that the book was a story, “a whole narrative of singular integrity and precise continuity; that is what makes the book so hard to put aside, even when one has come to the end.”

The film largely restricts itself to the late 1880s, the time of the Ghost Dance, a messianic movement that swept through the Plains Indian tribes. Within that period it weaves together three strands: the story of Sitting Bull, the legendary chief of the Sioux, who fought against Custer’s forces at Little Bighorn in 1876; that of Henry L. Dawes, the Massachusetts senator who pushed into law a plan to allocate portions of Indian land to individual tribe members; and Eastman, who was taken from his tribe by his father and attended Dartmouth and then Boston University School of Medicine.

It is in the last two stories that the film begins to bend history.

“Eastman was the most well-known, well-educated Indian at the beginning of the 20th century,” said Raymond Wilson, a professor of history at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kan., who wrote what is considered to be the definitive biography of Eastman. “When I heard they were doing the film,” he said, “I joked with a couple of people that I hoped they didn’t have Charles Eastman shaking hands with Sitting Bull at Pine Ridge.”

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home